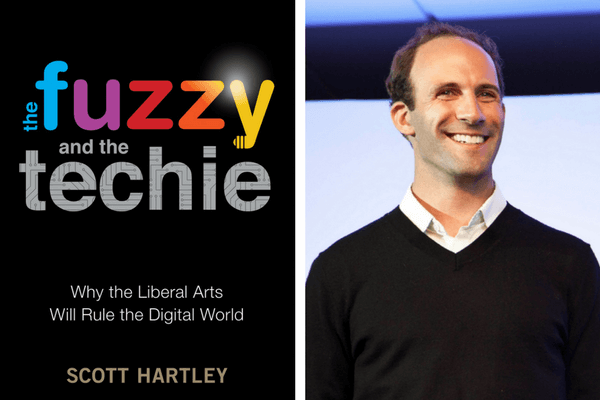

Scott Hartley is the author of “The Fuzzy and the Techie,” which explores how liberal arts graduates are having a profound impact on the development of new technology in places like Silicon Valley. Hartley first heard of the distinction between “fuzzies” (students of the humanities/liberal arts) and “techies” (science and tech folk) when he was a student at Stanford.

Hartley has worked at Google, Facebook, and as a White House presidential innovation fellow. He’s currently a venture capitalist and a fuzzy himself. He studied Political Science at Stanford and earned a Master’s in International Economic Policy from Columbia University. The NCMM caught up with Scott Hartley to discuss how students of the liberal arts are adding crucial value in technology by understanding human behavior and asking important questions about how technology gets applied.

This is an edited transcript of our discussion. For the full, unedited version, access the audio podcast embedded below.

What factors have traditionally separated these two cultures that you discuss in “The Fuzzy and the Techie,” and what’s changing the way tech people and humanities people interact now?

Hartley: The two cultures really go way back. Charles Percy Snow delivered a famous lecture in 1959 at Cambridge University where he said these two sides really need to have mutual understanding. Today the conversation has evolved into a faux opposition between technical and non-technical, hard and soft, liberal arts and STEM. The reality the book explains is that technology is not monolithically techie. There are so many contributors who are making it deeply human. For example, they’re using behavioral psychology to frame the choice architecture of how [digital] menu items are sorted in products. They’re doing user experience research to pull users and gauge interest and learn how to better develop a product.

The “soft subjects” like political science or history or economics are a mix of hard and soft. They involve statistical software and all sorts of independent and dependent variables, and teasing out the causes of complex things. In many ways, they’re not as soft as they might be framed. Computer science and mechanical engineering are also not as “hard” as they’re often framed.

What perspectives or methodologies do humanities people bring to solving the technical challenges a middle market company might face?

Hartley: In many of the social sciences, there are big issues around how we ask questions of data and how we question bias in how we’re pulling data. As we design algorithms, for instance, there’s this false assumption that because we code something into ones and zeros, and we pump it through this magical thing called an algorithm, that suddenly it becomes objective. But behind the scenes we need deep-thinking humans asking probing questions of where we’re getting data from. Is it biased in a certain way? How do we mitigate that bias?

I think that for any middle market company, familiarity with some of these new tools is important. Companies need people who’ve demonstrated engagement with data, engagement with technology, but they also need people who know the underlying methodologies learned through the social sciences. These people can ask important questions.

In what ways are middle market companies becoming more multi-disciplinary, blending fuzzies and techies, in approaching problems and setting up teams?

Hartley: There are so many different ways these worlds are converging. For example, the process of designing {digital] menus really relates to human behavior and what you think people will want and accept. There’s an example in the book of Sean Duffy, who founded a great company called Omada Health. Omada is aimed at reducing the risk of diabetes. Sean has a medical background and also worked at design firm IDEO, where he was focused on behavioral design.

What Sean found was that by nudging people to get off the couch and stay active, people can reduce body weight and change habits. Through the reduction of body weight came a 58 percent reduction in the occurrence of diabetes. This minor nudge in the behavioral process actually has this massive impact, not only on the lives and health of these people, but obviously on the cost savings for insurance companies. So that’s a great blending of fuzzy and techie.

How will emerging technology like automation and AI impact the jobs and tasks employees do at middle market companies?

Hartley: When you look under the hood of any job, there are certain best practices, certain codified tasks that are highly repeatable, and those repetitive tasks can be scripted. If they can be scripted, they can be programmed. If you look within your job and say “What am I doing over and over?” It’s likely there’s going to be some form of machine learning or other technology which will be able to do that faster and more efficiently than you.

So the trick is to evaluate within your middle market company or within your own role where you think these tasks are automatable, and then focus on the value added skills -- which are interpreting the data or being the human interface on collaborative elements of work.

What are the strengths that liberal arts people are bringing to leadership roles in middle market companies?

Hartley: Many. I’ll give one example. Slack is a corporate communications platform that sort of obviates the need for email, enabling better communication within your company. Slack was founded by Stewart Butterfield, who actually studied philosophy. Butterfield also founded a company called Flickr that was sold to Yahoo. He’s a great example of leadership when it comes to a liberal arts background. What he’s done is peel back the onion on what people want in the product, asking great questions. The product that he originally created was a gaming company, and through the iterative process of creating a company called Tiny Speck, he realized that this tool he was creating to coordinate internally between engineers was actually more useful than the gaming company itself.

Butterfield actually attributes his philosophy training to being able to change course, dig in on what this new product could look like, and then build a multi-billion dollar company, Slack. Obviously, Slack addressed a real pain point that Butterfield was able to put his finger on -- the email nightmare that’s in all our inboxes.

Any final thoughts for middle market leaders?

Hartley: Take a broader lens on this fuzzy vs. techie debate and realize that technology tools are becoming more and more accessible, it’s less about being able to leverage code and more about where and how we apply the technology. The epiphanies that led to high growth companies like Slack and Facebook are actually psychological or sociological in nature. Facebook really took off when they invented photo tagging because it created social dynamic and obligation where you got an email that says “You’ve been tagged in a photo.” and that drew users back into the platform. Similarly, Snapchat has created scarcity for a generation that’s only known digital abundance.

I hope that middle market leaders will recognize that if they understand a problem, small or big, better than anyone else, the technological tools are no longer the barrier. It’s understanding that problem at a deeply human level that’s their comparative advantage.

Listen to "Scott Hartley" on Spreaker.