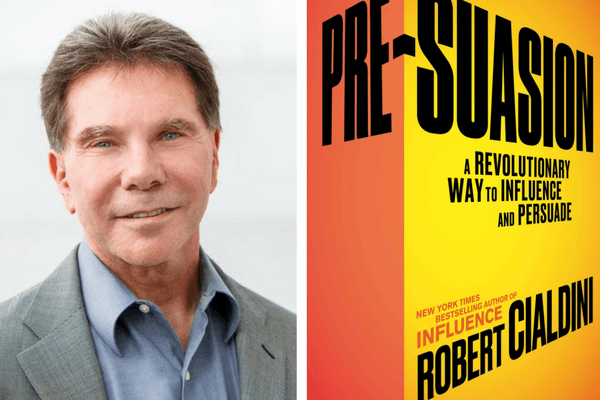

Robert Cialdini is a giant in the psychological study of influence, renowned globally for his groundbreaking and bestselling book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, as well as his pioneering academic research in the field of behavioral psychology. Cialdini is also CEO of Influence at Work, a company which trains individuals and organizations on how to be more influential. His new book, his first solo effort in three decades, is Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. The NCMM recently spoke with Cialdini about influencing others.

What is “pre-suasion”?

Pre-suasion is the process of arranging for others to be more receptive to a message before they encounter it. It works by creating a mindset in the listener that is consistent with the central element of your message before you send that message.

How might middle market company leaders benefit from understanding pre-suasion?

Pre-suasion will help you move from ordinary influencer, just focused on what you can say in your message, to extraordinary influencer -- by recognizing that what you can say or do before the message can ensure that your listeners will be susceptible to your message.

Can you offer some examples of how middle market leaders might influence their customers or employees through pre-suasion?

Sure. Suppose you have a brand new product or service, and you want to convince people to give it a try. What typically happens is that people hang back and are reluctant to try something that’s untested or unfamiliar. One thing you might do is ask people or the entire market whether they are adventurous. Simply by raising the concept of adventurousness, you steer people toward adventurous associations within your message, and they become far more receptive to your message about trying the brand new product.

Now suppose you’re an executive and you have a new initiative. You want one of your employees to lead this brand new initiative. One thing you might do even before describing the new initiative is to ask the employee whether they consider themselves an adventurous person. When that question is asked, 97 percent of people say “yes,” and now you’ve put the person in a mindset of wanting to follow opportunities to be adventurous. You will now get buy-in to a much greater degree than before you asked the adventurousness question.

You did a lot of interesting field research for the book. Can you explain what you learned?

I actually went undercover and infiltrated many training programs of businesses that seek to influence others, in areas like sales, advertising, marketing, management, fundraising, public relations, etc. As part of these training programs, we were often allowed to observe an old pro who was accomplished at doing business. I expected that these “aces” of these influencing professions would spend more time developing the specifics of their requests, its logic and its features. But that’s not at all what I found.

Instead, the highest achievers spent more time crafting what they did and what they said immediate before making their request. They went about their mission as skilled gardeners who know that even the finest seeds will not take root in stony soil. The best performers spent their time pre-treating the soil and making it ready for growth. That’s pre-suasion.

Business leaders don’t typically talk about mistakes or weaknesses, but your book cites this as pre-suasive. How so?

In a lot of situations, customers and our employees are skeptical about what we’re saying. I’ve learned from the research, as well as from observing what Warren Buffett does in all his annual shareholder reports, that leaders are likely to reduce the skepticism of listeners if they first make an admission of a weakness in their case. That causes people to view them as trustworthy communicators, so that when they present the strong points of their case, listeners are much more ready to believe them.

How can asking others for advice make middle market leaders more influential?

When we want to have a partner in an initiative, we commonly ask for someone’s opinion about it. This is a mistake. Instead of asking for an opinion, we should ask for advice. Asking for an opinion causes people to step back from us and reflect inside themselves, and so they psychologically separate from us. But asking for advice causes people to step toward us and approach the situation in a cooperative mindset. The behavioral science research is clear. If we ask for advice, people are more likely to support us than if we ask them for an opinion..

How might reflecting the word choices, cultural references, and common interests of listeners help middle market leaders be pre-suasive?

We’ve learned that people want to do business with those they like. And people like those who are like them. So if you have an audience with a particular orientation, or verbal style, or background, and you can find elements that you share with them, those people will be much more open and receptive to what you have to say. Using commonalities helps them like us.

You say at book’s end that organizations using pre-suasive techniques in an unethical manner, in self-serving ways which don’t advance the interests of customers, won’t succeed in the long-term. Why not?

Research shows that in organizations with unethical cultures, which usually comes from the top, a significant number of employees will leave because of a conflict between their own moral values and what the [unethical] organization expects them to do. The group of employees who are left behind will be comfortable with cheating, and they will cheat the organization too. They will steal equipment, and pad their expense accounts, and make “under the table” deals with suppliers.

If you allow an unethical approach to influence to take hold within your organization, employees who lie “for” you will also lie “to” you.