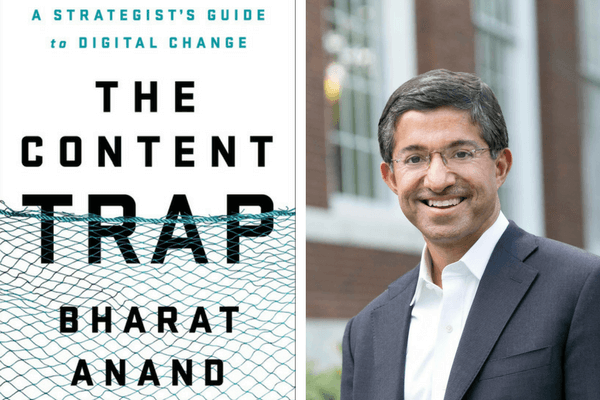

Bharat Anand, a Harvard Business School Professor and advisor to leading global companies, is a strategy expert who emphasizes connections above content (or products). Anand’s just-released book, "The Content Trap: A Strategist’s Guide to Digital Change," offers lessons for any middle market company navigating digital transformation. He fervently believes that connections and user-centrism will define business success in our digital age, not products. The NCMM spoke with Anand about his ideas.

What is “the content trap”?

It’s a mindset that companies fall into when confronting digital change. Their behaviors and decisions may seem rational at first but turn out to be flawed. First, companies might try to make the “best” product. Second, they might operate with increased discipline on what they do best, to deepen their focus. And third, they might track competitors and mimic them. All seem like plausible behaviors, but none actually work.

Connections matter more. So what wins in digital worlds isn’t making the “best” product but making products that connect people. Companies also need to recognize that value may migrate to new arenas where you should be playing, so just increasing your focus won’t work. Finally, mimicking your competitors won’t let you win, while being different might.

How is the content trap relevant for middle market companies?

These behaviors operate regardless of whether you’re a market leader or an entrepreneur or a middle market company. I do think there’s a classic tension between what’s been called “forget and borrow. Organizations confronting digital change must “forget” existing habits when needed and “borrow” existing strengths when needed, such as their brand or other assets. Very large companies find it extremely hard to forget, while very small companies have nothing to borrow. So middle market companies may therefore be in a better position to navigate this tension. They have some assets to leverage and borrow, but they’re also more nimble and thus more able to forget than larger firms. They’re in a strategic sweet spot.

What is the right mindset for middle market leaders facing digital transformation?

Disruptive forces are often about industry-level trends, but don’t necessarily define the fate of an individual firm. So strategy plays a big role in separating firms from each other. Ultimately, strategy is about the agency of managers. I’m both an economist and a strategist. If I put on my economist hat, and I look at traditional media for instance, it looks like companies are doomed. But when I put on my strategist hat, thinking as a manager, the only thing you can do is try to compete. As a strategist, you have to identify opportunities.

What are “network effects” and how might they create opportunities for middle market companies?

I talk a lot about this is my book. Network effects describe settings where the value of a product to a user depends upon the number of other users of that product. This is in contrast to traditional products where we measure the value in terms of quality and price. With networked products, the number of other users matters a lot. Think about purchasing an operating system or a multi-player game, where other users impact your buying decision. If you get ahead of others and win the network, it can be winner-take-all proposition and your growth can be exponential.

What are product “complements” and how might they create opportunities for middle market companies?

When growth slows down, many companies either raise prices or stop the bleeding by trying to fight whatever is causing buyers to go elsewhere. That’s a mindset that comes from focusing too narrowly on your product. Going elsewhere is often exactly where you should be going, since that’s where opportunity is migrating. Complements are about going elsewhere to capture value.

Look at what happened to music and CDs. If your firm focused just on CDs, you’d be doomed. But if you think about the complements to music, such as MP3 players and live concerts, those are arenas where value has migrated in significant ways. So companies that have gone through early phases of growth, and are looking to stimulate even more growth, will often be better off thinking about product complements rather than innovating on their existing products.

How can middle market companies identify product complements?

What is required is a shift in mindset from products to users. So let the user experience rather than product features define what your business is about. You’ll probably find that you’re in a much different business that what you’d thought.

For example, think about a famous tire company (Michelin) selling restaurant guides. If you focus on products, tires, that makes zero sense because it doesn’t make tires any better. But if you think about why and when people drive, then informing them about a great restaurant three hundred miles away makes fantastic sense as a complement. Now think about movie theaters offering childcare. On a product level, it makes no sense because babysitting is not a theater’s core business. But if you think about why a family might stop going to the movies, then childcare makes a superb complement.

Many middle market companies prefer saying “yes” to customers, but your book makes the strategic case for saying “no.” Why?

You must prioritize which customers you seek to cater to, because you can’t cater to everyone. Wal-Mart, for example, offers its customers value for money and a wide product selection. But a near-universal customer complaint about Wal-Mart is its bad store ambiance. But if Wal-Mart invested in improving its store ambiance, they’d sacrifice what they do best, low prices and wide selection. Saying “no” on certain things allows you to say “yes” to others.

Why do you warn against middle market companies embracing “best practices”?

The danger of embracing best practices is when they don’t relate to your customer’s most important needs. On dimensions that your customers truly care about, you should seek to be “best-in-class,” but on dimensions your customers don’t prioritize, then don’t try to be best-in-class -- it’s just a matter of efficient resource allocation.

For instance, Wal-Mart should never benchmark on store ambiance because that’s not a top priority for its customers. Best practices should depend upon the context and strategy of each company, and the priorities of its customers.