Vienna Beef Ltd. (http://www.viennabeef.com/) was founded in 1893 when two Austrian-Hungarian immigrants introduced their family frankfurter recipe at the legendary Columbian Exposition. The hot dog was a hit, and Vienna Beef was born. Today, Vienna Beef is much more than a hometown Chicago sausage maker: Vienna Beef manufactures a variety of foods under a number of brands, has a global footprint, and represents an intriguing middle market success story. We recently spoke to Tom Pierce, Director of Marketing at Vienna Beef about some of his company’s unique successes and challenges.

Tell us a little about the background of Vienna Beef. How did the company get its start?

Tell us a little about the background of Vienna Beef. How did the company get its start?

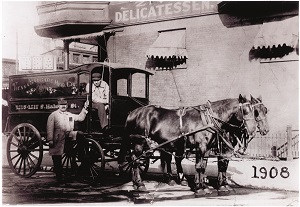

In the 1890s, there were a couple of immigrants from Vienna, Austria (hence the name) who immigrated to the U.S. to set up a sausage business surrounding the World’s Fair Columbian Exposition in 1893. They had a food stand at the exposition, and about 27 million people visited the fair, which is an amazing number for back then. They were so successful and there were ample supplies of beef here, so they stayed in Chicago and set up their sausage business and delicatessen business. It’s been a family owned, privately held company continuously for 123 years, based here in Chicago. It’s basically the same family; the original two partners passed it onto two sons, and then a son-in-law and his partner bought it in the 1970s after the death of the two brothers. Those two gentlemen still own it today.

Vienna Beef is a very old company. How do you balance the need to honor your company’s traditions and history, while still evolving with changing consumer tastes and needs?

You have to know who you are and what you stand for, and what your brand means to your customers. We’ve always tried to be known as a very high-quality, very high-consistency product that doesn’t vary even though the raw materials may change. Over the years, the diets of animals have changed, the tastes of our customers have changed, and we’ve become a more homogenous society. We’ve had to change as our customers change, but we can’t change the taste of our product, that’s who we are. What we’ve done is we’ve diversified; we’ve gotten into the kosher pickle business for example. That line of production fits exactly with our delicatessen beef offerings. We make things the old, traditional ways: corned beef, roast beef, pastrami, hot dogs. We’ve also diversified and gotten into the soup and chili business, to make authentic deli style soups to supply to our customers. So I think one of the challenges has been to respond to our customers as their tastes change. You have to adjust to that and keep up with the times: new packaging, innovations, new marketing. We have the stuff that everybody else has— a web presence, online business, t-shirts and hats to support our brand, and we never had that stuff 50 years ago. You have to grow as your customer grows. The way we’ve kept relevant is to follow our customers.

become a more homogenous society. We’ve had to change as our customers change, but we can’t change the taste of our product, that’s who we are. What we’ve done is we’ve diversified; we’ve gotten into the kosher pickle business for example. That line of production fits exactly with our delicatessen beef offerings. We make things the old, traditional ways: corned beef, roast beef, pastrami, hot dogs. We’ve also diversified and gotten into the soup and chili business, to make authentic deli style soups to supply to our customers. So I think one of the challenges has been to respond to our customers as their tastes change. You have to adjust to that and keep up with the times: new packaging, innovations, new marketing. We have the stuff that everybody else has— a web presence, online business, t-shirts and hats to support our brand, and we never had that stuff 50 years ago. You have to grow as your customer grows. The way we’ve kept relevant is to follow our customers.

Your website mentions Vienna Beef’s global expansion. Can you talk about what exporting looks like for your company, and how you’ve selected markets for international expansion?

I just mentioned following our customers, and that’s how we’ve managed to enter overseas markets. It’s usually a customer who comes to us, who’s confident in our product here in the States and says they’re going to open up a franchise in Abu Dhabi or Japan (or something) and asks us to supply them in that market. So we respond, and if it’s viable, it’s something we can do without jeopardizing our product, we look into it. We spend the money on research and development and testing, but we would never send a bunch of salesmen and marketers to Japan without any business to go develop a market. We’re too small; we don’t have the money to do that. A big, national corporation may do that, but we don’t operate that way. It’s not good or bad, just that we don’t operate that way. But if a customer pulls us into the market, we’re more than happy to go and keep their business that way. We’re in the Middle East— in the UAE and a couple of other countries because Shake Shack is there and we make the sausage for them. We followed them into the market, so that they could sell the same product they sell here. It works out for all of us.

How does Vienna Beef think about growth – organic only? Acquisition? Has the company ever been a target for acquisition?

It happens in various ways. Because we’re over 100 years old, we probably have seen every scenario over the years. We’re in the relationship business; we’ve had customers that are much bigger than us who have asked to take over and said they could triple the size of the business. We’ve had companies much smaller than us come and say that they have a really good soup or pickle business, and they need someone Vienna’s size to help them grow. We get it from both ends, and we’ve taken advantage of that over time. For example, we’ve been in the soup business for well over 30 years. Now we moved into a new factory, and our soup capabilities are 10x what they were in our old factory, so now we have more of a purpose to go look for new business, instead of just looking for our customers to need more. We’re always changing our tune to better our company. I’ve been at Vienna for 45 years, and I’ve been in a lot of food plants across the country. I know you expect me to say this, but we make really, really, really good food. When we find a product or a new product or something going on in the marketplace, we look for what can we manufacture but keep our standards along the way. We’ve made mistakes, but we’ve also recovered from them.

It happens in various ways. Because we’re over 100 years old, we probably have seen every scenario over the years. We’re in the relationship business; we’ve had customers that are much bigger than us who have asked to take over and said they could triple the size of the business. We’ve had companies much smaller than us come and say that they have a really good soup or pickle business, and they need someone Vienna’s size to help them grow. We get it from both ends, and we’ve taken advantage of that over time. For example, we’ve been in the soup business for well over 30 years. Now we moved into a new factory, and our soup capabilities are 10x what they were in our old factory, so now we have more of a purpose to go look for new business, instead of just looking for our customers to need more. We’re always changing our tune to better our company. I’ve been at Vienna for 45 years, and I’ve been in a lot of food plants across the country. I know you expect me to say this, but we make really, really, really good food. When we find a product or a new product or something going on in the marketplace, we look for what can we manufacture but keep our standards along the way. We’ve made mistakes, but we’ve also recovered from them.

What are some unique advantages and challenges of working for a middle market company?

Competition is one of the biggest challenges. As more conglomerate-sized companies gobble up small manufacturers and distributors, it puts the little guy out of business. The small jobber who distributes specialty foods, it’s very hard for him to compete on the same scale as the big national restaurant suppliers. He doesn’t have the scope to get to every corner of the country at the same time. You have to follow your heart and do the best you can, and out-service the big guys. Our quality speaks for itself, but we can’t just rest on our reputation either. People eat our product and it’s gone next week. We want them to buy it again, and run their restaurant and know that they can count on us to have exactly the same thing that they built their business on. You have to earn the business over and over again.

him to compete on the same scale as the big national restaurant suppliers. He doesn’t have the scope to get to every corner of the country at the same time. You have to follow your heart and do the best you can, and out-service the big guys. Our quality speaks for itself, but we can’t just rest on our reputation either. People eat our product and it’s gone next week. We want them to buy it again, and run their restaurant and know that they can count on us to have exactly the same thing that they built their business on. You have to earn the business over and over again.

What’s next for Vienna Beef? What are you most excited about?

We are in our new home; we’re in just our third address in 120-some years, so we’re not really good at moving. We moved almost a year ago now. We could’ve moved out of Chicago; and cut our labor costs in half and built a cheaper plant and gotten tax incentives and things. But our company is made up of 250 employees and their families, who have worked for us for generations. There’s a lot of pride in what they do every day. We didn’t want to pack up and move someplace because it was cheaper. Our workers really are the best of the best in their industry. And we’re just proud to stay in Chicago, even though sometimes that’s challenging. We’re lucky, Vienna’s got a great name, there’s a lot of romance behind it. Even though you can get our hot dog in 800 hot dog stands, everyone’s got their favorite one. There’s a memory that’s attached to all of this, and we could never see ourselves walking away from that. It’s a challenge to be in a new location, so we’re just getting used to it being our home. We’re looking at how we can make things smarter, and faster, and make new things without disrupting what we do in our regular day.

Settle it for anyone outside of Chicagoland: does ketchup have a place on a hot dog?

Personally, I don’t care what you put on a hot dog. As long as it’s a Vienna hot dog. The wisdom is that if you’re going to have a Chicago hot dog: you’ve got tomatoes and onions and relish and all that stuff on it, the acidity of the ketchup camouflages the taste of the fresh vegetables. Mustard doesn’t. Taste is personal, but there’s science behind it. Part of it is history; immigrants didn’t use ketchup when they were selling sausages on the street. They had vegetables that they could buy cheaply and put on top of a hot dog. But ketchup was a little bit difficult. Mustard came with the hot dog from Germany, from sausage makers in Europe. My grandkids put ketchup on their hot dogs though.